CAN-SPAM, America’s anti-spam law, was designed to be business-friendly and set a low bar for compliance. Not heavily enforced during its 14-year existence, the Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act of 2003 requires brands to, among other things:

- Include a working unsubscribe link in every promotional email they send

- Honor opt-out requests within 10 business days

- Include their mailing address in every email they send

- Never use misleading or deceptive sender names, subject lines, or email copy

- Never attempt to conceal their identity or the fact that they’re sending advertising

Noticeably absent is any kind of requirement for businesses to get permission from consumers before sending them mass commercial emails. Businesses only need to provide a way for consumers to opt out from receiving such emails.

Moreover, to keep states like California from passing stronger anti-spam laws that would raise standards and make compliance more complex, CAN-SPAM stipulates that it is supersedes any state-level anti-spam laws.

In September of 2017, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reviewed CAN-SPAM and had a request for comment period regarding “the efficiency, costs, benefits, and regulatory impact of the Rule.” No changes have resulted from that review, which is unfortunate because we believe CAN-SPAM’s lax regulations have done U.S. businesses much more harm than good. Here’s why, and how we think the FTC can fix the law.

What CAN-SPAM Has Done

First, without a strong law to help rein in spam, inbox providers were left on their own to control the assault of spam hitting their mail servers. In response, they created the “report spam” button and junk folders. Later, they created engagement-based email filtering. Now, inbox providers like Gmail use hundreds of signals to determine whether to block, junk, or deliver email to inboxes.

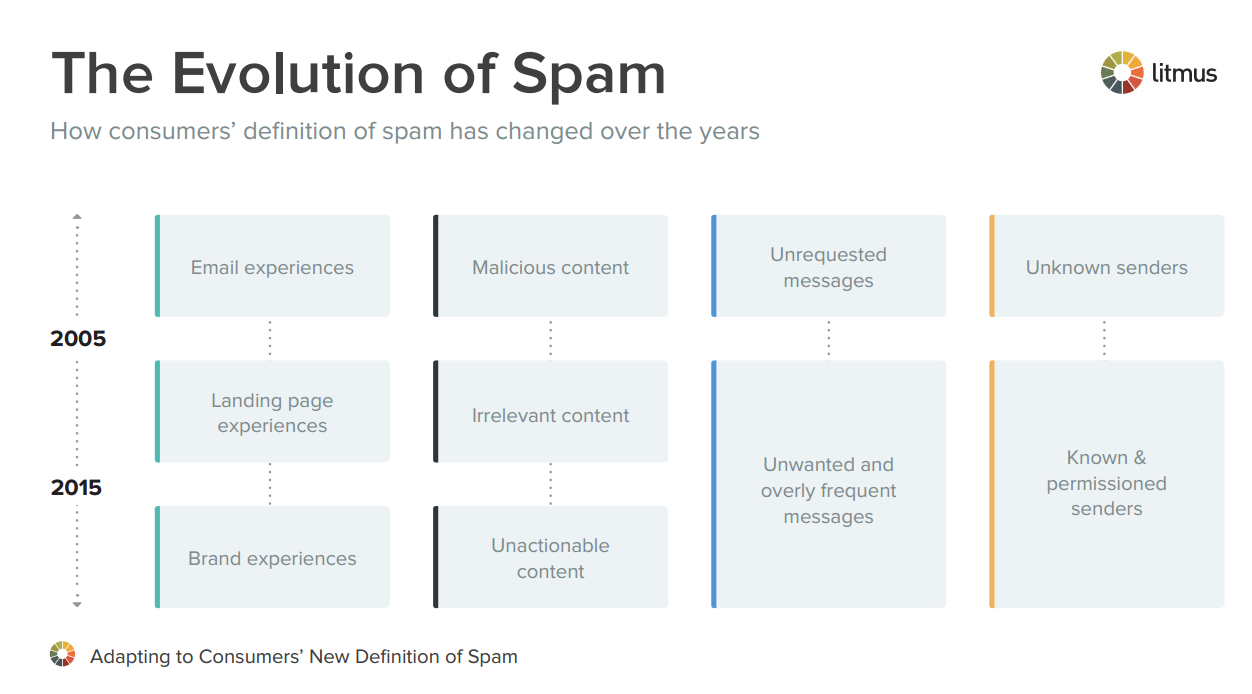

Their efforts have led consumers to dramatically redefine what spam is. The spam of 2003 is now a small portion of the spam that consumers are battling.

One could argue that the current deliverability system is a triumph of self-regulation, since email users rarely ever see truly malicious spam, such as virus-bearing attachments, make it to their inbox. One would also be correct in arguing that the current system is a disjointed patchwork of spoken and unspoken rules that make ensuring deliverability overly difficult for legitimate senders. Moreover, virtually all of the burden and costs of stopping spam, which still accounts for the majority of all email sent, falls unfairly on inbox providers such as Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Verizon.

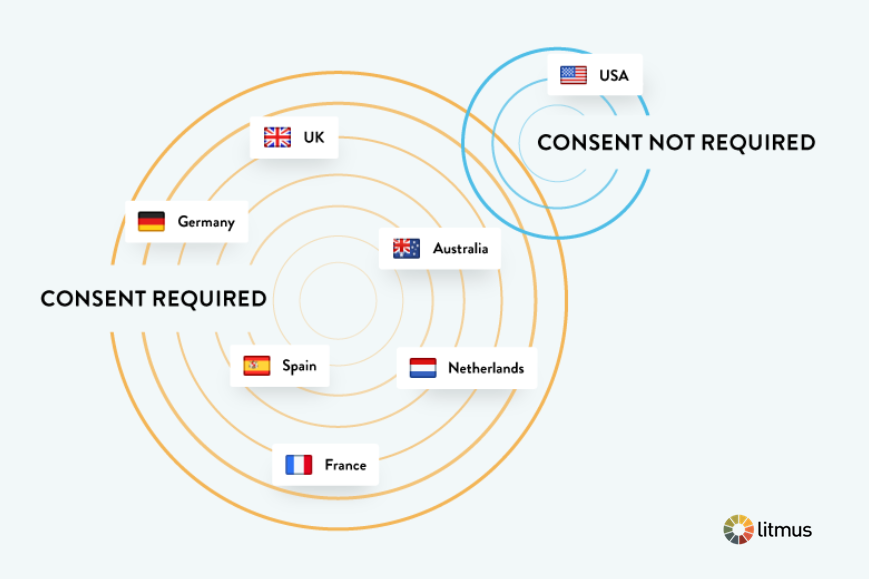

And second, CAN-SPAM’s incredible weakness created a regulatory power vacuum that caused other nations to pass much stricter laws to compensate for the America’s inaction. Most notably, Canada passed the Canadian Anti-Spam Law (CASL), which completed the final phase of its rollout in July, and Europe is currently in the process of rolling out its latest privacy law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Germany, Australia, and other countries have passed tough anti-spam laws as well.

These laws are based on where the recipients of emails are located, not where the sender is based. So U.S. companies have to adhere to these laws when their subscribers are in Canada, Europe, or elsewhere. That fact has confused some U.S. brands, who are all but guaranteed to be in violation of international anti-spam laws because U.S. laws lag so far behind international laws.

And U.S. senders who are aware of the differences have a tough choice: Taking on the risk of trying to comply with laws at different ends of the spectrum with different processes for different subscribers based on geolocation, or creating a uniform, less-risky, and easier-to-manage process based on the more restrictive international laws.

The unintended consequence of CAN-SPAM is that it has exposed U.S. brands to greater deliverability and legal risks.

[ Tweet This →]

CAN-SPAM is woefully out of step with subscribers’ current behaviors, email service providers’ current capabilities, inbox providers’ current demands, and the laws of other countries. In truth, if a brand only clears the low bar set by CAN-SPAM, they are pretty much guaranteed to be blocklisted and blocked by inbox providers.

While on the surface, lax regulations look like an advantage to American brands, it’s really setting them up for failure. The law can do better for U.S. businesses.

What CAN-SPAM Should Do

CAN-SPAM needs to not only close the gap with other international anti-spam laws to help simplify compliance for global U.S. brands, it needs to promote practices that will help businesses grow and avoid the wrath of consumers and inbox providers. Here are seven suggestions for how the Federal Trade Commission can improve CAN-SPAM:

1. Make it clear that opt-outs should be honored “as soon as possible” and narrow the deadline for honoring opt-out requests to 3 business days.

The reason for the current 10-business-day opt-out window in CAN-SPAM was to accommodate highly distributed organizations with batch-based systems. Technology has improved vastly since 2003 and this accommodation isn’t necessary anymore.

Also, consumers expect brands to honor opt-outs immediately, so allowing 10 days to honor unsubscribes suggests to businesses that it’s okay to continue sending email to consumers who have explicitly said they no longer want to receive email. While we wrestle with how to define spam here in the U.S., there’s no doubt that sending email to people who have opted out is spam.

The FTC should not legally sanction a 2-week-long window when sending spam is okay when there’s no technological or operational need. A 3-day window should accommodate those that need extra time while setting better expectations for sender behavior.

2. Dictate unsubscribe practices more clearly.

The Online Trust Alliance’s 2016 Email Marketing & Unsubscribe Audit makes it clear that brands are not consistently doing a good job of making it easy to unsubscribe.

Those inconsistencies have translated into consumer confusion, as 39% of Americans say that unsubscribing from brands’ promotional email is either “difficult” or “very difficult,” according to Litmus and Fluent’s Adapting to Consumers’ New Definition of Spam research. Consumers 65 and older were more likely to be affected, with nearly half (48%) saying they find it difficult to opt out of email. As a result, 50% of consumers say they’ve resorted to clicking the “Report Spam” button because they couldn’t easily find out how to unsubscribe.

Firmer expectations need to be set, such as:

- Unsubscribe instructions and the unsubscribe link should be in a paragraph separate from offer details, administrative text, and other copy in the email footer.

- Unsubscribe instructions should use a font size at least 2 points larger than text appearing before and after it.

- Unsubscribe links should include the word “unsubscribe” to aid in link identification.

- Unsubscribe links should always be created using HTML text, never as a graphical button, so unsubscribe links are visible when images are blocked.

- Unsubscribe pages should clearly identify the brand/sender and the email address that is being opted out.

- Unsubscribe pages should allow subscribers to opt out of all emails from the sender with a single click.

- List-unsubscribe headers should always be included in emails. Most email service providers already add these to their users’ emails by default.

3. Expand the definition of transactional emails to include non-promotional post-purchase emails.

CAN-SPAM currently defines an email as transactional if it consists only of content that:

- Facilitates or confirms a commercial transaction that the recipient already has agreed to;

- Gives warranty, recall, safety, or security information about a product or service;

- Gives information about a change in terms or features or account balance information regarding a membership, subscription, account, loan or other ongoing commercial relationship;

- Provides information about an employment relationship or employee benefits; or

- Delivers goods or services as part of a transaction that the recipient already has agreed to.

To accommodate the emergence of non-promotional post-purchase emails such as installation instructions, product care instructions, and product review requests that relate directly to a purchase, the definition of transactional emails should be expanded to include:

- Provides information about the installation, usage, or care of a purchased product similar to that contained in the product’s instruction or owner’s manual on a one-time basis

- Asks for feedback or a review of a purchased product or service on a one-time basis

These updates would remove the legal risks associated with these relevant and highly accepted emails, and the “one-time basis” language would make it clear that senders can’t abuse these emails by sending a series of emails related to these topics.

Beyond those updates to the existing language of CAN-SPAM, the scope of the act should be widened to include these additional provisions that will reduce spam and make email safer:

4. Require CAPTCHA on all open email signup forms.

Unprotected open email signup forms allow spammers, hackers, and other bad actors to use bots to weaponize email, as we saw in the August 2016 attack that led to dozens of blocklistings by Spamhaus. Only 3% of sites examined by the Online Trust Alliance used CAPTCHA to reduce the risk of bot signups and “list bombing.”

CAN-SPAM should require all open email signup forms to be protected by some form of CAPTCHA, whether it’s traditional CAPTCHA, reCAPTCHA, or some other similar device. That will help protect email users and businesses.

5. Mandate authentication and in-transit encryption.

Fueled by new powerful analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, email personalization is on the rise and will be a potent part of email marketing’s future. Hyper-personalization and automation was a major theme of our Email Marketing in 2020 report, which asked 20 experts what the channel will look like at the end of the decade.

However, the downside of this trend is that it makes consumers more susceptible to phishing if these emails are compromised and consumers can’t tell who’s sending them emails. Phishing costs businesses $500 million a year, according to the FBI.

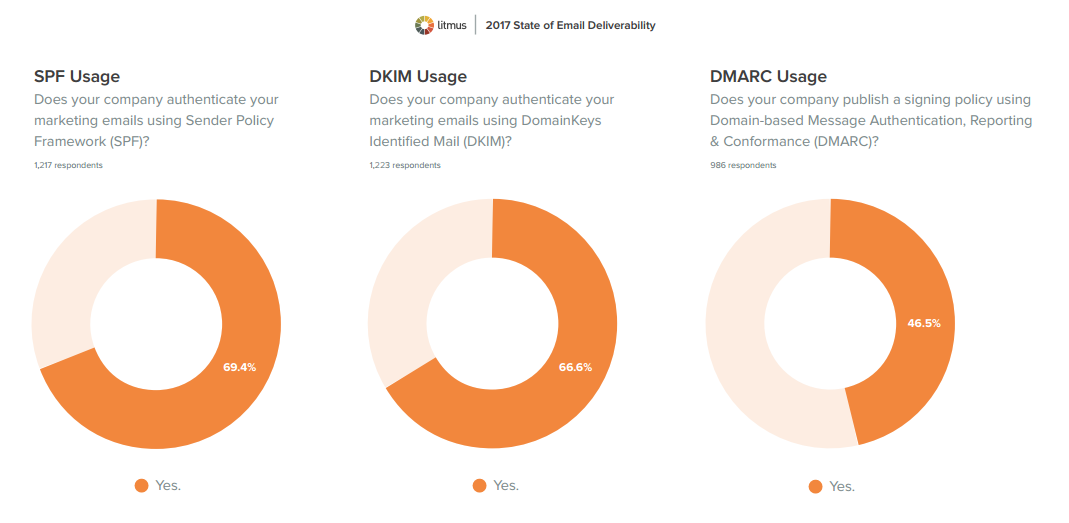

CAN-SPAM could reduce these costs and help protect businesses and consumers by mandating that senders authenticate their emails using all three existing standards: Sender Policy Framework (SPF), DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM), and Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance (DMARC).

Despite being created more than a decade ago, SPF and DKIM are used by less than 70% of brands, according to Litmus’ 2017 State of Email Deliverability research. And not even half of brands are using DMARC.

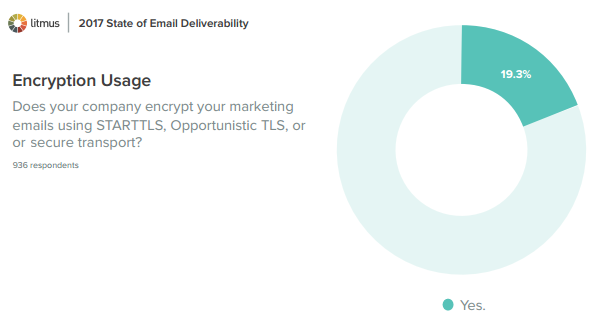

In addition, to protect email content while emails are in transit, CAN-SPAM should require senders to use Opportunistic TLS and secure transport encryption. Currently, fewer than 20% of marketers encrypt their emails.

6. Require consent or an existing business relationship.

Most international laws require marketers to collect permission from the owner of an email address before sending any communication. CAN-SPAM, on the other hand, doesn’t have any kind of permission requirement.

To simplify compliance for American businesses, unite North America under a single permission standard by adopting the definitions and regulations in CASL around expressed and implied consent and existing business relationships.

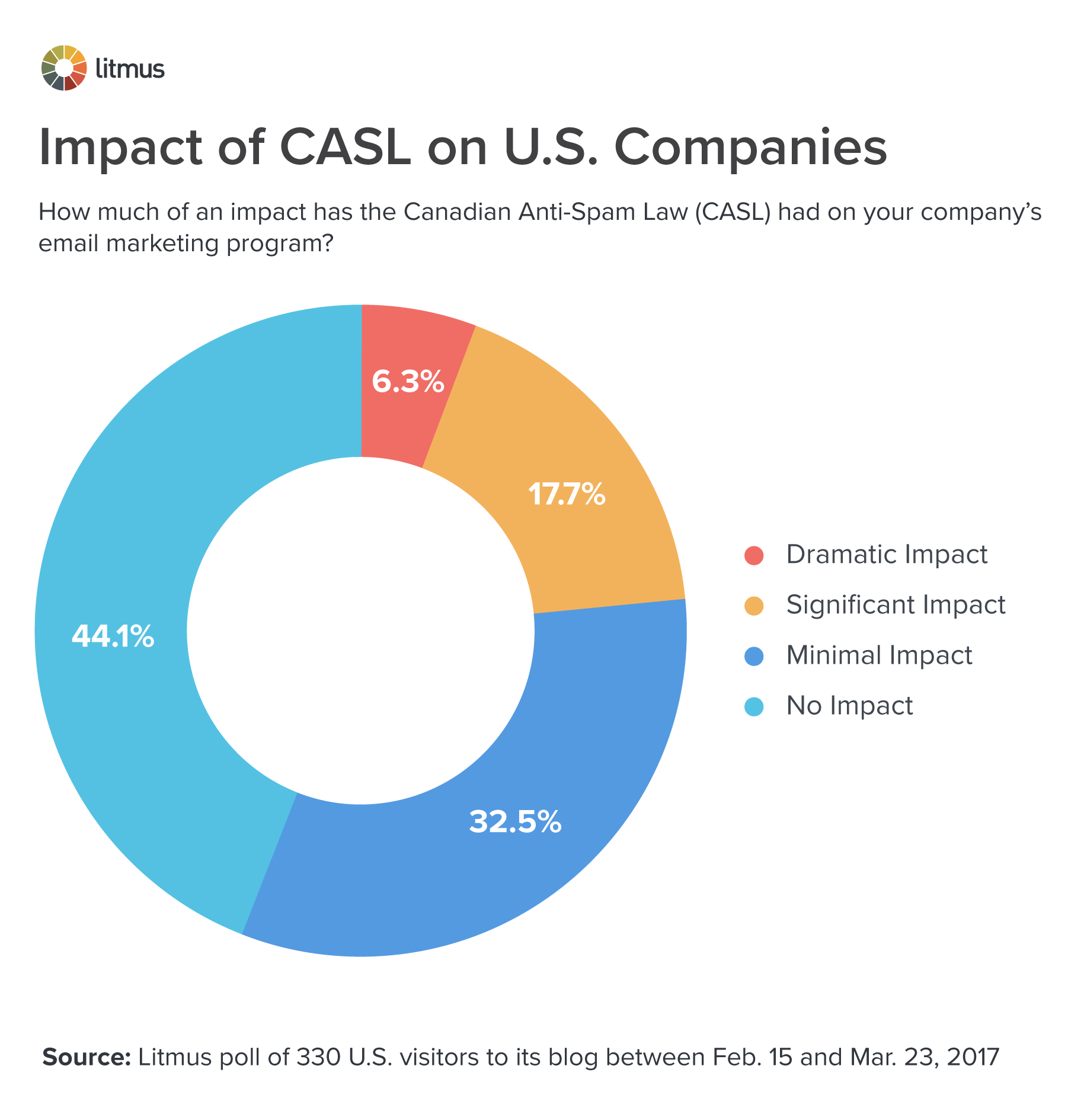

CASL is already impacting the majority of U.S. brands, according to a Litmus poll of more than 300 U.S. marketers. And since large companies are more likely to market to Canadians, the impact is even higher if looked at from a revenue-weighted perspective.

Requiring permission would drastically cut down on risky email acquisition practices. For instance, 17.4% of brands have purchased an email list in the past 12 months and 9.4% have rented an email list (which often looks very similar to a list purchase), according to Litmus’ 2017 State of Email Deliverability report. Both of those are among the riskiest subscriber acquisition sources.

Moreover, whether we like it or not, globalism is dragging permission standards higher for U.S. companies. Resisting that pull is becoming pointless, diminishes our ability to influence international laws, and complicates compliance for American businesses. Plus, tighter permission regulations would also help Americans to keep their inboxes free of messages they don’t want.

7. Stipulate that prolonged non-response is the legal equivalent of opting out.

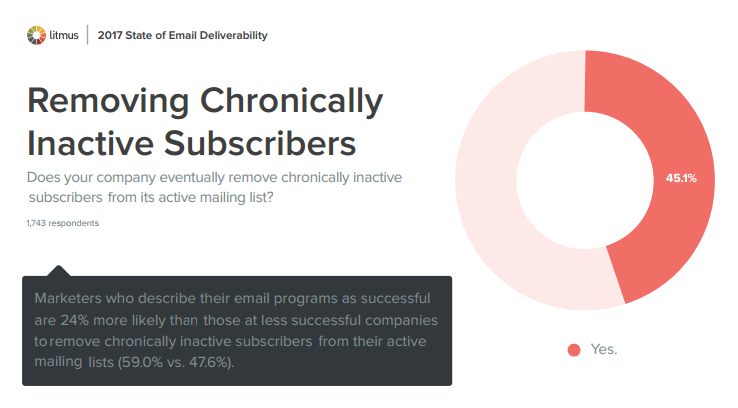

In addition to recognizing the need for permission, CAN-SPAM should recognize that permission expires. Most marketers don’t ever stop emailing chronically inactive subscribers who have long since stopped opening or clicking their emails, according to Litmus’ 2017 State of Email Deliverability research.

Engagement is a significant component of inbox providers’ filtering algorithms, so this behavior harms brands’ deliverability as well as contributing to America’s high spam volumes.

To set better sender expectations, CAN-SPAM should require senders to stop emailing subscribers when they haven’t opened or clicked an email in the past 2 years. Considering that 80.7% of brands that send re-permission campaigns to inactive subscribers do so after 15 months or less of inactivity, a 2-year window is incredibly generous.

U.S. marketers are open to stronger regulations

These changes are necessary because while the incredibly permissive CAN-SPAM Act was intended to be pro-business, the fact is that it’s so out of step with consumer expectations, industry best practices, and international laws that…

CAN-SPAM has harmed U.S. businesses

and made inboxes less safe. The

@FTC should strengthen it.

[ Tweet This →]

Many marketers recognize this need, with nearly 47% of marketers expecting U.S. anti-spam laws to be strengthened by the year 2020, according to Litmus’ Email Marketing in 2020 report. If you’re one of them, help us let the Federal Trade Commission know by sharing the tweet above. And if you have suggestions on how CAN-SPAM should be updated, please share your thoughts in our community discussion on U.S. anti-spam regulations.

Disclaimer

This post provides a high level overview about CAN-SPAM, but is not intended, and should not be taken, as legal advice. Please contact your attorney for advice on email marketing regulations or any specific legal problems.

The info in this blog is 2+ years old and may not be updated. See something off? Let us know at hello@litmus.com.

Chad S. White is the Head of Research at Oracle Digital Experience Agency.